Rubén Valdez

Practice for Architecture

You’ve been based in Switzerland for some time now. What does it mean to you—personally and professionally—to return to Mexico through the act of building?

Being born and raised in Mexico, and introduced to architecture from an early age through my father, who is an architect, I developed a deep-rooted connection to the Mexican built and unbuilt environment. My first three years of architectural education in Mexico further solidified this connection and shaped many aspects of my personal and professional identity. Although a series of serendipities eventually brought me to Switzerland, there are many aspects of my personal and professional culture that were nurtured by those experiences in Mexico and that are difficult to apply elsewhere, so it was really important for me to be able to build back home as a cultural and personal connection to my country.

How do you navigate the idea of belonging? Do you ever feel split between worlds?

It is a personal crisis of mine this sense of belonging…….. both professionally and personally. I definitely feel split between two worlds, and although it is enriching it is also very difficult to manage, and very lonely as there are very few people that share this kind of situation. Specially between Switzerland and Mexico.

“In projects like Paradero, or more recently in the projects I’ve started in the Bahamas, designing every single detail is crucial. Poor detailing can completely undermine the experience.”

How does working from a distance shape your perception of Mexico as a cultural and architectural landscape? Does that remove give you clarity—or create tension?

Both, it is undeniable that living outside of Mexico and having also a formation in contemporary art, gave me a very different perspective of both the Mexican and Swiss architectural practices. I think the important thing in this aspect is to learn how to navigate between complementarities, contrasts and contradictions in order to make the most out of this binational situation. Having said that, Mexico is going through a great moment art and design wise, it is really enriching to discuss with colleagues and friends from there and somehow be part of a scene which is becoming more and more relevant worldwide.

You move fluidly between roles—architect, artist, educator, publisher. Do these identities shift depending on where you are, or are they constant across contexts?

Until recently, my professional life was pretty clearly split by geography—I spent eight years teaching at EPFL, nine years as editor of Cartha magazine, and worked on various collaborations with artists, all of it happening in Switzerland, while most of my architectural practice was based in Mexico. But that changed quite a bit recently. I won a competition for a school center here in Switzerland with my wife and partner in this project, which is now in the planning phase, and another one for the entrance and third building of the Plateforme 10 museum cluster in Lausanne. Around the same time, I stopped teaching at EPFL and became less involved with Cartha. I’m still working on projects in Mexico and abroad, and now I’m also a guest lecturer at ECAL, but I’ve started taking on a role here in Switzerland that’s much closer to what I’ve been doing in Mexico as an architect. I do hope that one day my work as an educator, editor, and artistic collaborator can also grow more on the Mexican side of things too…

What was your first encounter with the Baja California Sur desert like—not as a visitor, but as someone about to build in it?

I think it’s hard to think of my connection to Baja only as someone who’s about to build there. I lived in La Paz ( Capital of Baja California Sur) for four years during my childhood, and my family used to visit Todos Santos regularly. My mom was a paleographer working in the historical archives of Baja California Sur—she specialized in translating documents from the first missionaries, from old Spanish into modern Spanish. So when I arrived to work on the area, I already had a pretty unique and privileged understanding of it, one that went beyond just an architectural reading of the site.

The construction process sounds unusually tactile—on-site concrete mixing, hand-cast forms, rough finishes. Was that a practical decision, or a philosophical one?

I try not to separate practical decisions from philosophical ones—pretty much every act in the construction process has consequences that go beyond just the material side of things. In that sense, the choices we made regarding construction methods and finishes were grounded in what made sense for that specific context—materially, ecologically, and from a human standpoint. We also considered how to make the most of the available resources and skills from an architectural perspective. As mentioned in the previous comment, architecturally speaking the idea was to have the building feel as if it had emerged from the context, so all of the material choices, were aimed to feel less “artificial” or “pristine” in a context that’s actually quite raw and rugged.

Paradero doesn’t just sit in the landscape—it seems to grow out of it. What kinds of spatial or emotional ideas were you working with in designing something that feels so embedded?

The first signs of built architecture in the area were the Jesuit Missions, which basically followed a central courtyard typology — all the programming was arranged around the perimeter of the courtyard, creating a balance between collective and individual experiences. They used this layout to protect themselves from the wilderness of the Baja California Desert, while also creating a controlled natural environment within the courtyard. At Paradero, that historical precedent is kind of flipped. Our relationship with unspoiled nature today is totally different — instead of trying to keep it out, we’re trying to embrace it. That shift informed a lot of the design decisions, both in terms of typology and scale.

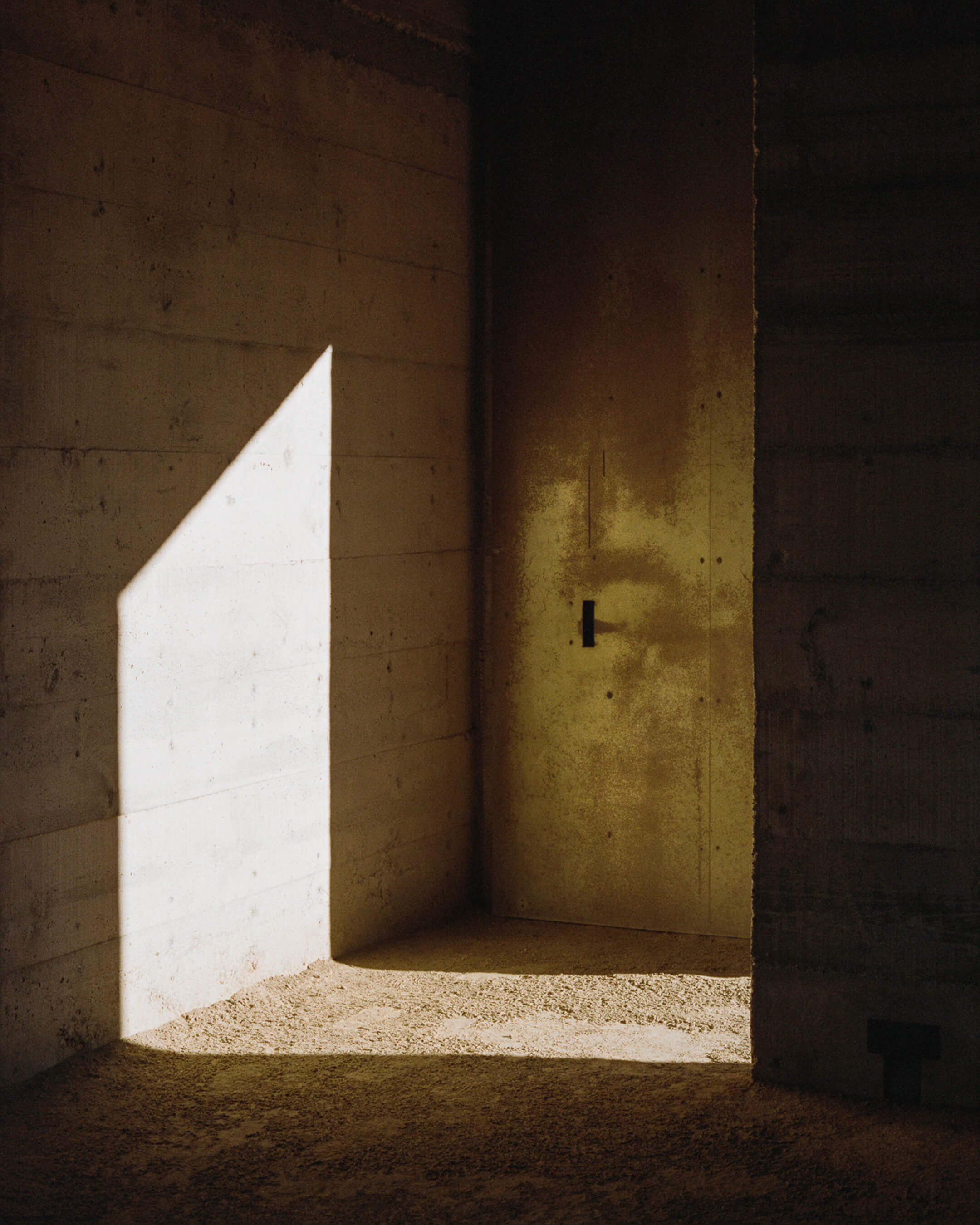

That said, it was really important that the architecture had an abstract quality — something that didn’t immediately resemble any specific kind of building. The idea was for it to feel like a sculptural, inhabitable ruin — something that looks like it’s always been there.

This feeling was reinforced through what I call the "disarticulation" of architectural elements. By that I mean, in some areas — like the entrance — there’s no floor at all, and the walls just rise straight out of the earth. In other places, columns go directly into the ground without any plinth or flooring. Some spaces are roofless, some don’t even have walls…the classical architectural elements are treated as an open inhabitable system which is intertwined with the landscape.

On top of the material choices, this disarticulation really helped the building feel like it’s emerging from the site, not just sitting on top of it.

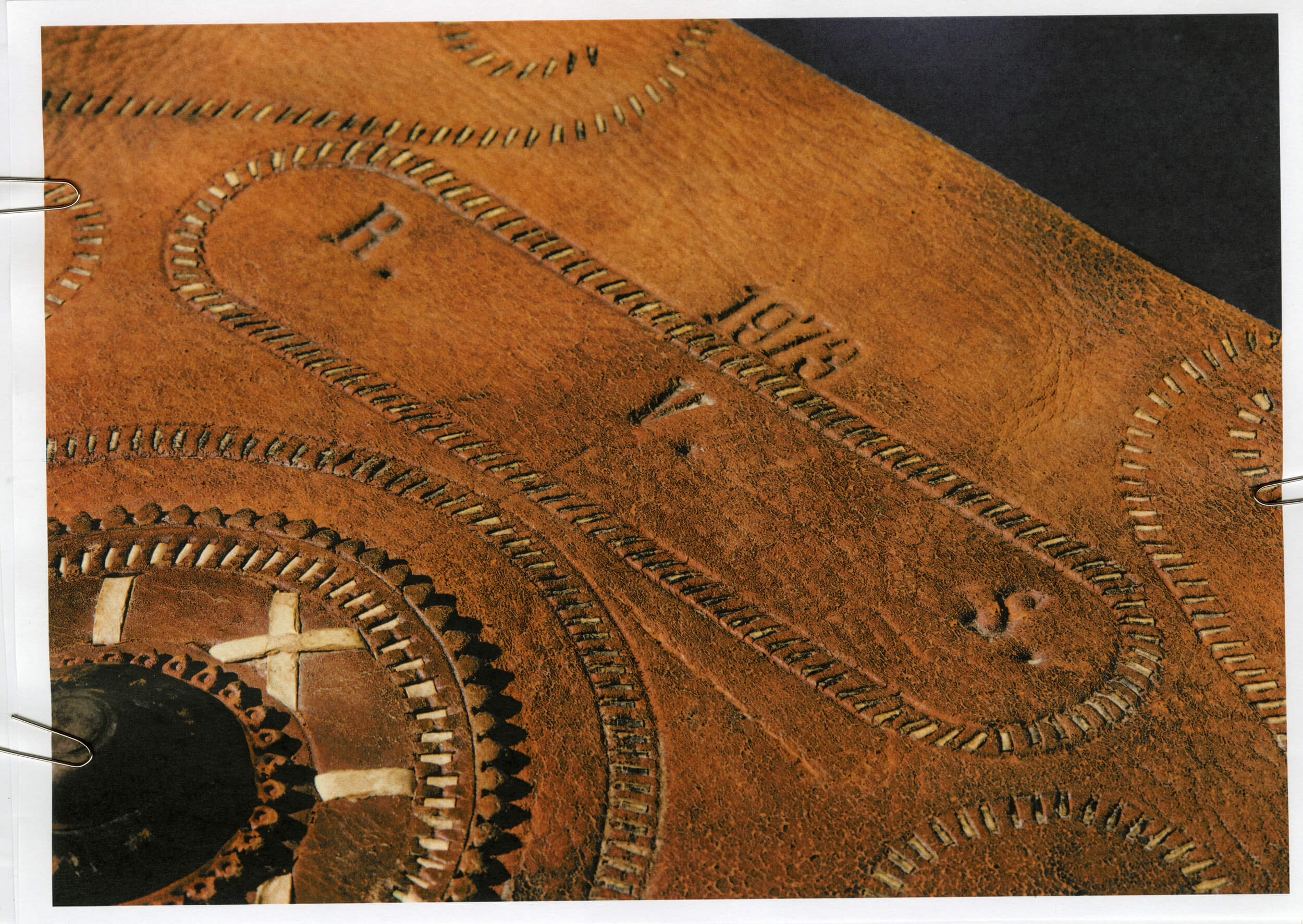

“This bag belonged to my great-uncle Ramiro Valdez Sanchez, a priest in rural Mexico. It was made in 1973 by a local leatherworker and used by him for about three decades before passed away. Many of the objects I keep around serve as reminders of my origins and my family's journey—something that deeply influences me both creatively and personally.”

You’ve described the project as an act of ecological restoration. How do you see the relationship between architecture and repair—both environmental and cultural?

In the context of the global climate crisis — and considering that around 40% of global CO2 emissions come from the built environment — it’s crucial that, as architects, we aim to reduce the negative impact of our projects as much as possible.

In the specific case of Paradero, the site used to be an intensive farming plot located right next to an incredible cactus forest. So, we had this amazing opportunity to benefit from a beautiful natural setting without damaging it. On the contrary, we were able to transform the former farmland into a desert garden that still includes some farming, but in a way that significantly boosts the site’s biodiversity.

Now, architecturally speaking, it might seem a bit contradictory to talk about building a luxury hotel out of concrete in the context of sustainability — and I get that. But we were very intentional about minimizing the impact of both the program and the material. For example, the project uses about 30% less built area per room compared to other hotels in the same category. We used 10 cm-thick concrete walls, which helped cut down on material usage — reducing overall concrete consumption by 20 to 50% compared to standard methods. We also built on less than 7% of the total surface area of the site and relied heavily on passive climate strategies, which greatly reduced the need for air conditioning.

Culturally speaking, I think the value of the project lies in reimagining what a high-end hospitality experience can be — less about materialism and consumerism, and more about care, contemplation, and introspection. I don’t know if that entirely makes sense in the current global context, but that was definitely one of the core goals of the project — and a clear intention from the clients as well.

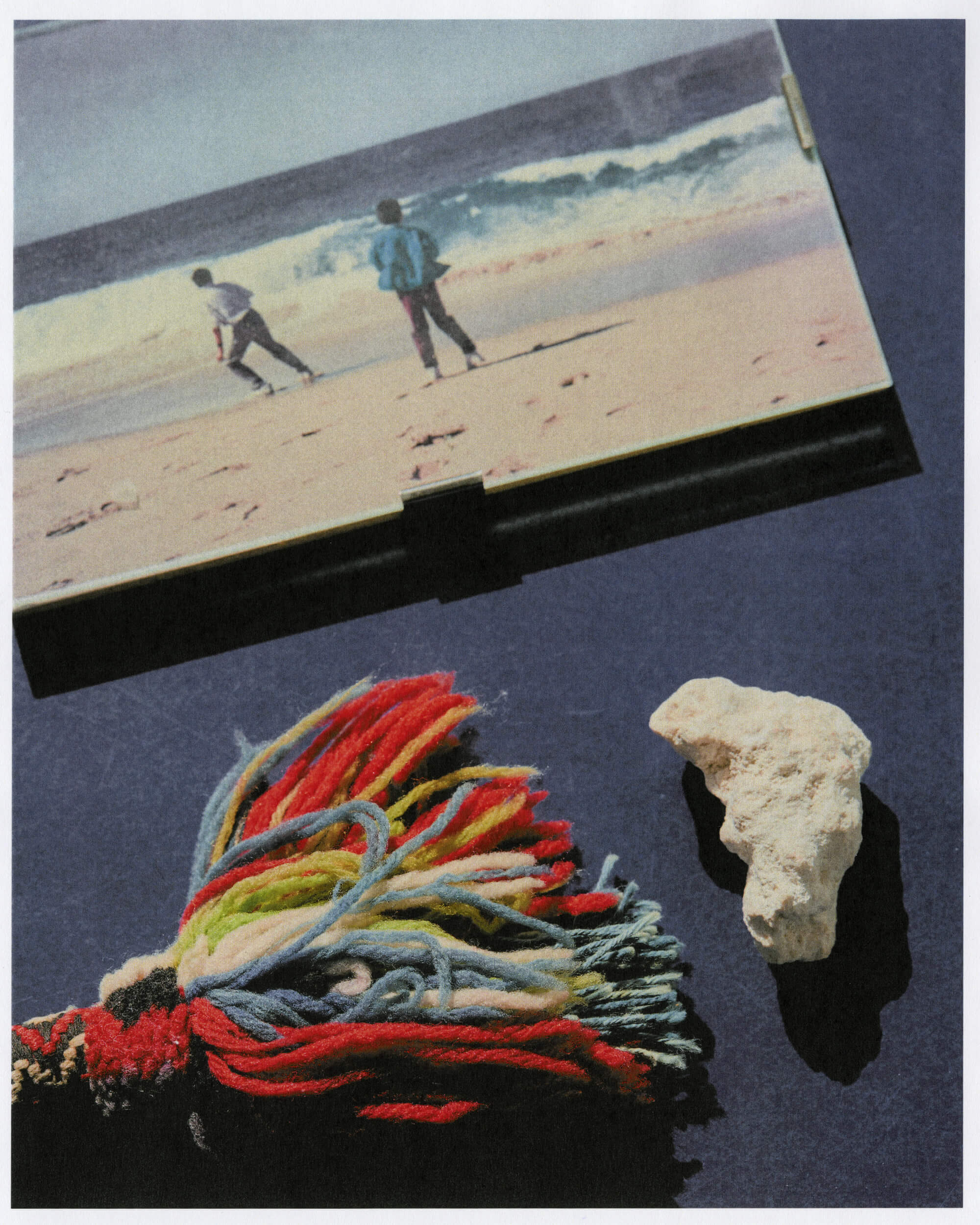

“This photo shows my brother and me in the Pacific Ocean in Todos Santos, where Paradero now stands. I keep it nearby because it’s remarkable that we played in the same town where I would design and build Paradero and the spiritual enclosure 30 years later ! The stone beside it is from the island I’m working on in the Bahamas. The fluffy item is part of a bag made by my great-grandmother on my mother’s side about 100 years ago. She passed it down to my mother, who then gave it to me.”

Both Paradero and the Spiritual Enclosure seem to embrace a slower, more porous idea of space—open air check-ins, earthen floors, filtered light. What does comfort mean to you in a place like this?

I think that after COVID — and in the middle of a global context that’s honestly pretty grim — some people (or at least the kind of people who go to Paradero) are finding comfort in different things. Contemplation, silence, nature… those things feel way more comforting than a 52’’ TV or a coffee maker in the room. I think most of our generation feels that way, too.……But I also believe comfort isn’t just about amenities or perks — it’s about creating a wholesome, intentional experience. That means architecture plays a role not just as a visual or spatial element, but as an agent that allows for multiple ways people can connect — with each other and with nature — regardless of how “precious” or expensive the materials are. On a personal note and contributing to this wholesome intentional experience, I also got to curate part of the music that’s played in the hotel’s common areas, which follows that same line — calm, introspective, and rooted in a sense of stillness.

That said, there were five things the clients were very clear about having at the highest possible level: the best mattress and linens, great water pressure and temperature in the showers, perfect toilet flush, reliable high-speed internet, and exceptional food and drinks. Once those essentials are in place, you actually have the freedom to be as minimal, and monastic as you want — and still create a comfortable and luxurious experience.

The circular ceremony space feels especially stripped-back and meditative. What were you hoping visitors would feel—or not feel—when inside it?

I think for our generation, spirituality has taken on a completely different meaning than it had for our parents. It’s much less tied to any specific religion or faith, and more about personal introspection, connectedness and moments of quietude. In that sense, and in line with the overall ethos of the hotel, the idea of contemplation was pushed much further in the design of the ceremony space.

Architecturally, I wanted to create a strong sense of seclusion and detachment from the outside world. From the exterior, all you really see is a single entrance and a 1.2-meter-high concrete element emerging from a low mound in the desert. The entry sequence is intentionally disorienting — you walk in through a baffled entrance that's offset 45° from the main axis, which gradually descends and reveals the space.

Inside, you step into a 3.6-meter-high circular enclosure that’s open to the sky, with a bare earth floor that reinforces a kind of transcendental connection to both the ground and the cosmos. The only visual opening is a carefully placed semi-circular aperture that frames a mountain to the west. Just below it sits a polished obsidian mirror, inspired by the texcatl mirrors used in pre-Hispanic Mexican cultures for reflection and spiritual divination. It’s the only symbolic object in the space, offering a layer of meaning that doesn’t rely on religious iconography.

It’s a pity that it can’t really be captured in a photo, but the space also works beautifully for stargazing too. The circular opening — 12.5 meters in diameter — is the same as the field of view you get when lying at the center and looking straight up. It creates a kind of frame for the night sky, which is actually a really moving experience.

I’ve always been fascinated with the infiniteness of the universe and how we are part of it….in this sense this project is about creating an experience that sees spirituality as something cosmic, not necessarily religious.

You collaborated with landscape architects, interior designers, and artists on these projects. What’s the most important ingredient for creative alignment when everyone brings a different language to the table?

I think sharing the same values and goals is absolutely key. Many of the values that guided the creative decisions or the project where shared, so even though we were all speaking different "languages," we were aiming for the same thing, which made the collaboration feel very natural. Then of course although it may sound like a cliche, communication and trust are key aspects in any collaboration around complex projects such as this one.

Do your experiences as a publisher and educator change how you approach collaboration in the field? Is there a curatorial aspect to how you build a team?

They definitely have an impact on my practice, but I’d also say that having studied art really helps when it comes to collaboration, as I spent two years talking with people that had nothing to do with architecture. This definitely helped in trying to understand and find common ground with other creative disciplines.

In the case of the Paradero project, the team was chosen collectively, so I wouldn’t necessarily call that a curatorial practice of my own. In a new project I’m working on in the Bahamas, I do have the chance to choose every member of the team — so yeah, in that case you could say it’s more of a curatorial process. Still, like I mentioned earlier, what I’m really looking for, are collaborations where we share similar values but bring different, complementary perspectives to the table.

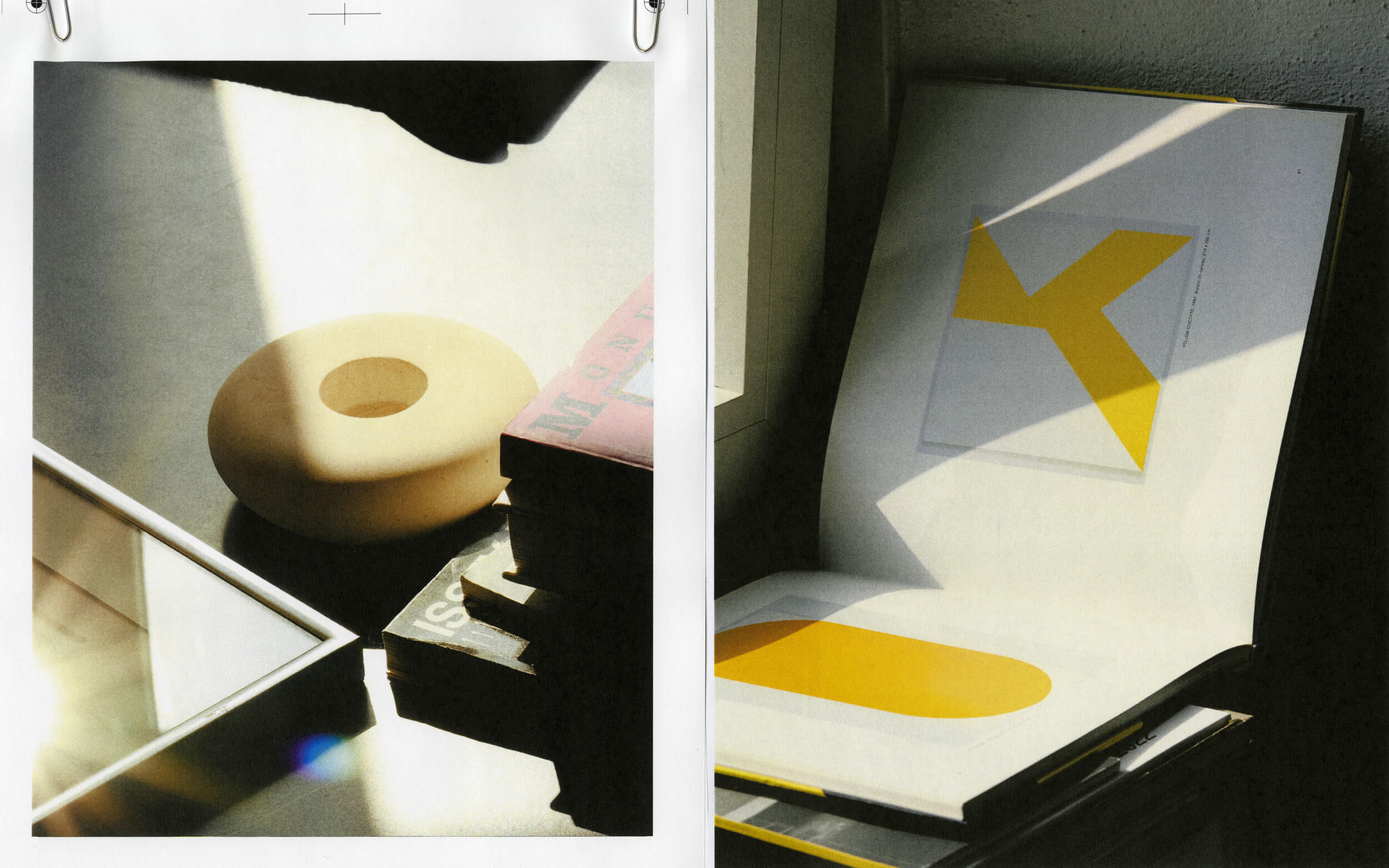

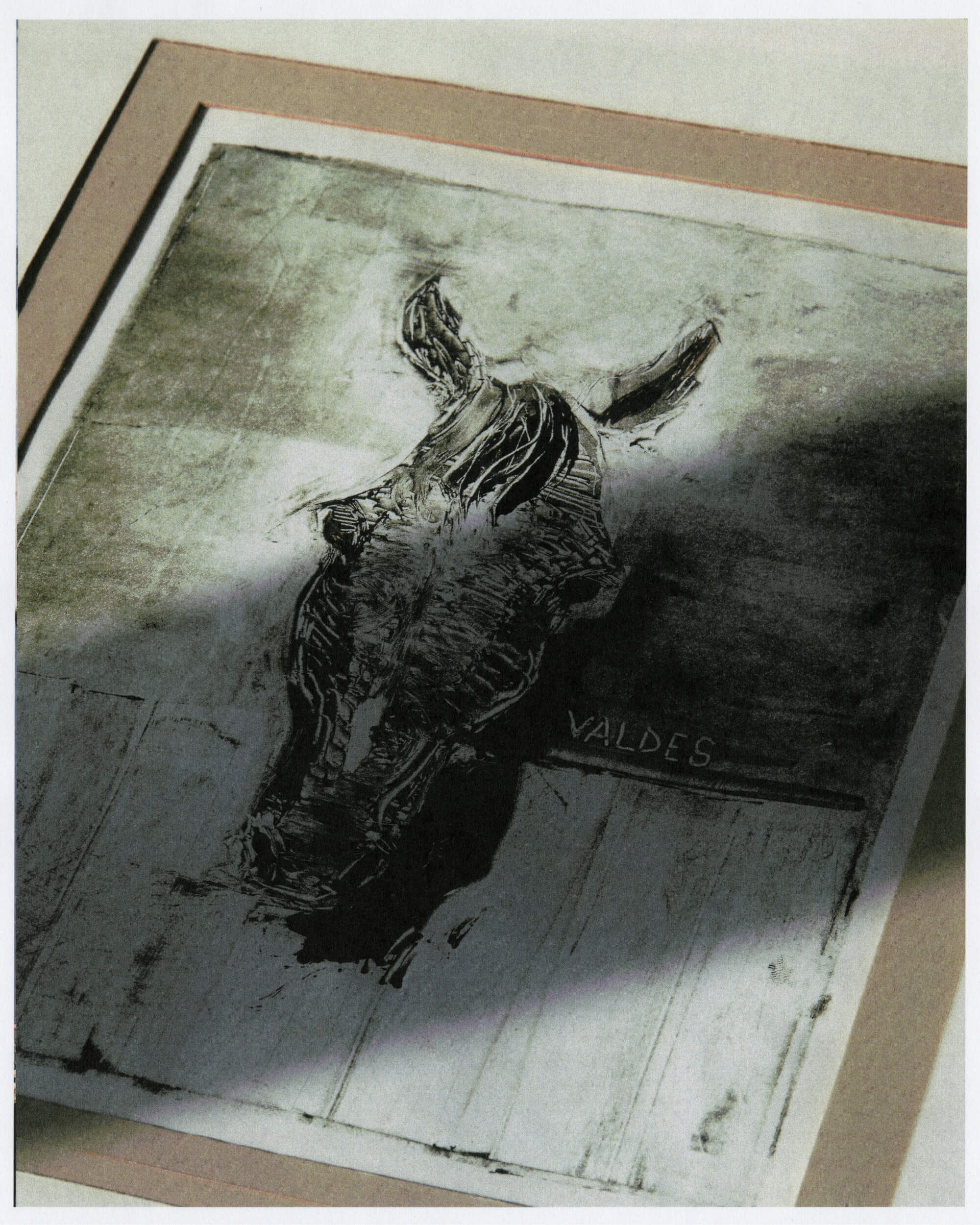

“This is a drawing of a horse by my father, who was not only an architect but also an experienced horse rider, having grown up in a very remote town in the mountains of Jalisco.

He had a profound influence on my creative sensibilities—not only through his architectural work but also through his drawings, sculptures, and his vast collection of books and records, which shaped me from an early age.”

Architecture can carry so many stories—of place, identity, ecology. What’s the throughline you're trying to weave across your work today?

When I studied contemporary art at ECAL around 2012 I met Julien Fronsacq (who was then curator at the Palais de Tokyo) and Stéphanie Moisdon, who works closely with artists and curators involved in the relational aesthetics movement, such as Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno, among others. With both Julien and Stéphanie, we often met with these artists and visited their exhibitions. This had a strong impact in my work and the way that I saw architecture. Just as in relational aesthetics, where the artist is seen as a facilitator rather than a maker, I try to see my practice not necessarily as the construction or creation of architectural objects, but rather as a spatial practice that re-defines the built environment through the set of relationships that give space its agency. This has informed the design and realization of my projects, which rather than relying on a specific architectural language, consistently explore how spaces are activated or deactivated, their affordances, and the dynamic relationships they both influence and are influenced by.

Spiritual Enclosure, Ceremonial space, Todos Santos 2024. Architecture by Rubén Valdez, Photography by Cesar Bejar.

Paradero, Hotel, Todos Santos, Mexico, 2021. Collaboration with Yashar Yektajo, Landscape architecture by Polen Arquitectura de Paisaje, Interior design by B-Huber. Photography and film by Gillian Garcia, Art direction by Florine Bonaventure. © Rubén Valdez

Interview by Sebastian Vargas, Portrait images by Louis Victorin Michel for Profiler.